|

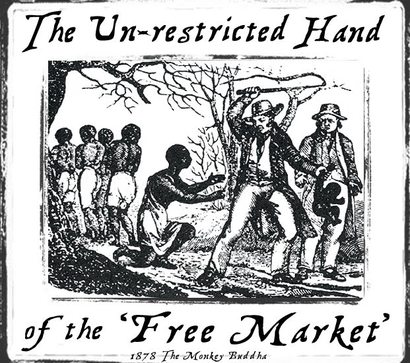

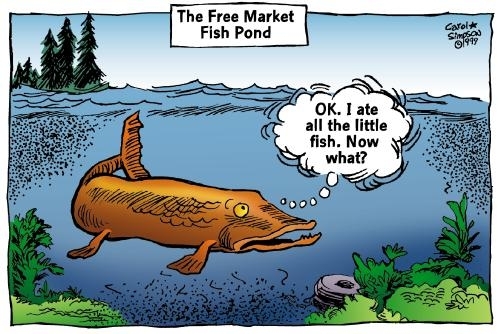

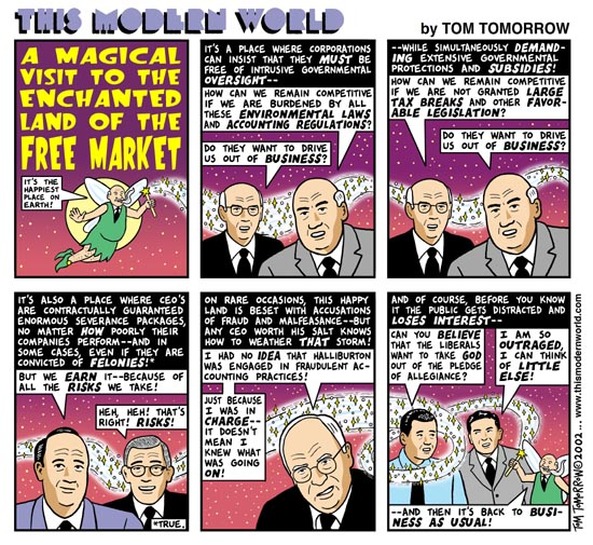

I am going to make this short, because Robert Reich has already said what needs to be said in this space (here). My role here is to punctuate the obvious. Let's start with what people believe. The "Free Market" The formal definition of a free market goes something like this: A market system in which the prices for goods and services are set freely by consent between sellers and consumers, in which the laws and forces of supply and demand are free from any intervention by a government, price-setting monopoly, or other authority. A free market economy is a market-based economy in which prices (for goods and services) are set freely by the forces of supply and demand and gravitate to their point of equilibrium without intervention by government policy. It typically entails support for highly competitive markets and private ownership of productive enterprises. Free markets are also often associated with capitalism. However, the concept has been championed by anarchists, advocates of cooperatives and socialists. Sounds Good To Me. (What is Your Problem, Buddy?) I agree. It sounds wonderful and fanciful. And it is exactly that. Apart from the assumptions that are made in the definition of free market, which do not exist in any country on Earth, people in societies that embrace free market capitalism also assume that the "free market" is natural, not man-made, inevitable and not influenced by the government. This means that the outcomes of the "free market", i.e. inequality, poverty, insecurity, famine, war, etc, is beyond our control. This is all fiction. The Reality At the core, the “free market” is a set of rules that specify:

The rules defined above are a mere subset of the complete set that go into creating a "free market". These rules do not exist in nature. They are creations of the minds of men (and women). Markets are not “free” of rules. The rules define them. As citizens of a democratic society, we have a say in the "free market". We help define the rules in a number of ways, including voting governments into power, Government help to organize and maintain the rules that create the "free market". Let me repeat this for emphasis: Governments don’t “intrude” on free markets. They facilitate free markets. But? But? But? But NOTHING.

Ask yourself why there is no longer a (public) market for African slaves, why young children are not delicacies at your favorite restaurant, why urine-inspired beverages are not all the rage at your local watering spot or why your water supply is not filled with faeces and bacteria. Now, own your part in creating and evolving our "free market". Now, realize that you are responsible for the consequences of the "free market" (as it exists today). Yes, you share responsibility for inequality, poverty, crime, homelessness, etc. Let that sink in. Now, do something positive about it.

2 Comments

Over the last few weeks, I had the pleasure of chatting with Aneesh Chopra - the first Chief Technology Officer of the United States of America - on a number of topics related to Skills, Workforce and Innovation. One of our earlier conversations included the state of job postings online. Aneesh energetically (and nonchalantly) observed that it was all a house of lies - where job matching and or job scraping company after company would forage for as many job postings as possible, ingest them into their own (proprietary) systems, and create business value from them. This got me thinking. Are companies who are advertising jobs in their firms aware that:

In 2011, Citi estimated the online recruitment market size to be $3 billion globally. In November of 2013, Staffing Industry predicted the global staffing market to exceed $422 billion by the end of 2013, with 30 percent ($12.6 billion) coming from the U.S. So, I am guessing that a lot of companies are either unaware of (or unable to do anything about) the widespread theft and misappropriation of job listing data. Why? Because for a market of that size, firms that are aware of this would be constantly in litigation to maintain their data ownership rights and keep their IP. What I find even more fascinating is the slippery slope (of admitting that data ownership matters).

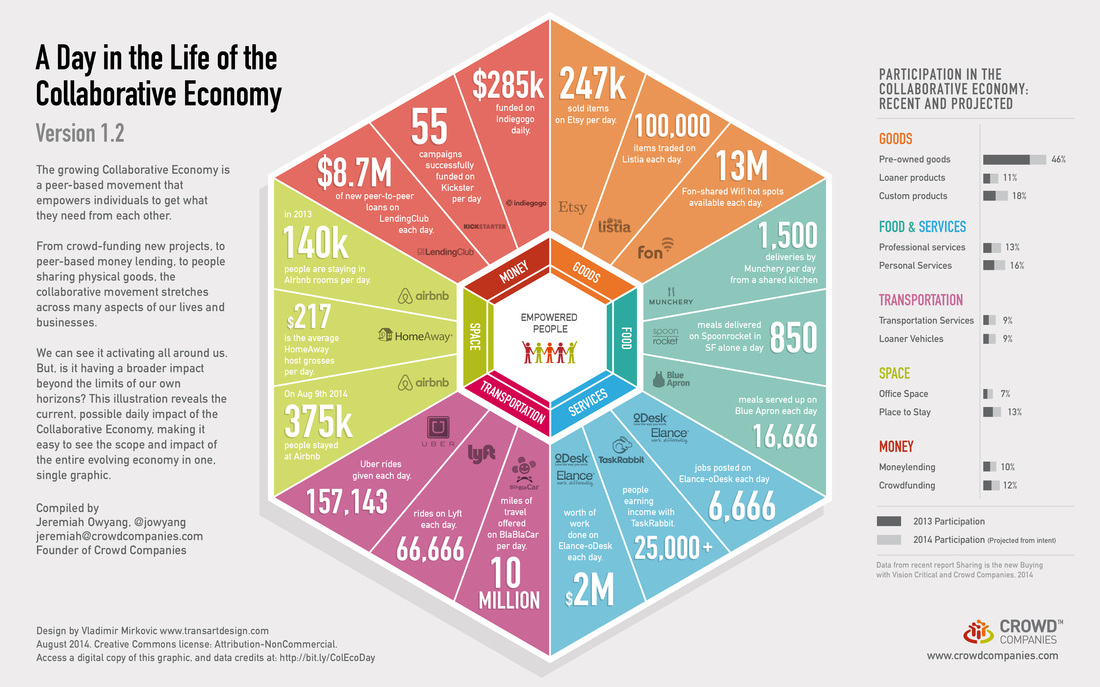

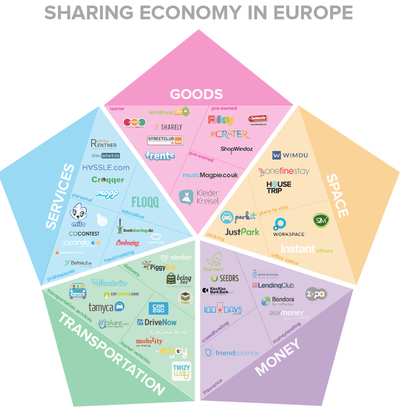

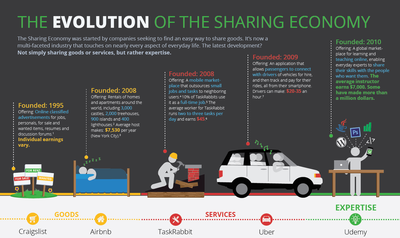

Once firms start taking this seriously, will they then have to admit that they are stewards for the data they receive from their clients/users (and not data owners in that context)? What do you think?  I had the pleasure of meeting FCC Commissioner Ajit Pai at a dinner reception a few weeks ago at the Residence of the Swedish Ambassador. He struck me as a personable, funny, intelligent, and kind (family) man, who recognized the need for innovation and was not afraid to leverage other people with expertise in areas that complement his own expertise. He mentioned the impending vote on Net Neutrality and mentioned the raised levels of interest from everyone about the topic. He seemed excited, eager and earnest about voting on the issue and doing the right thing. When You Assume Now imagine my shock when the decision came down and I learned that he voted against the measure. (You can read his full dissent here and a summary of it here). I thought to myself: "What could have led him to this decision?" I read his full dissent statement (and the summary) multiple times to try to figure out how someone so smart could come to a No on this initiative. Were there details, i.e. fine-print, in the proposal that I (and the public) were not being told about? I struggled with this for a long while and debated if I should say anything at all. Unfortunately, my curiosity could not let me rest. Just to ensure that everyone is on the same page and that we are all talking the same language, let me start with the basics. Back to Basics What is net neutrality? It is the principle that Internet service providers, specifically cable companies, should enable access to all content and applications regardless of the source, and without favoring or blocking particular products or websites. But? But? But? Isn't this how the Internet has always been? Yes, you are correct. We always had net neutrality ....... until some companies decided that it would be more profitable to have different levels of service that they could charge for; where some traffic would be fast and others not-so-fast. I won't re-hash the entire story in this blog. The interested reader can get more here. But? How could companies do this? Legally, there was no one to stop them. Broadband was not regulated under the same rules as the telephone lines (which the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) deemed had to remain open). What Does the FCC decision mean? The gist of what the FCC did in the last week of February 2015 was to finally side with the American people. (The story is more complicated, as all current relationships, with the FCC being against Net Neutrality before they were for it) The FCC said "America you can continue to have net neutrality". However, they said it in a way that killed all the legal ambiguity surrounding the issue. Now, companies know that if they try to play favorites or to monetize the Internet wires that there will be penalties to pay. So now you are all caught up. So how could anyone disagree with this? The Dissent Ajit's dissent starts off with a single true sentence and then immediately pivots: For twenty years, there’s been a bipartisan consensus in favor of a free and open Internet—one unfettered by government regulation. So why is the FCC turning its back on Internet freedom? It is flip-flopping for one reason and one reason alone. President Obama told it to do so It is true that a free and open Internet has been a bipartisan issue (or rather a non-issue). It is true that it has been unfettered by regulation. It is also true that until recently, the broadband providers did not realize the transformative nature of the Internet and were not innovative enough to capitalize on the ecosystem that grew on top of their infrastructure. After the success of a few Internet companies, like Google and Facebook, broadband company executives sought a way to get a piece of their revenues. After all, these companies were using their wires for very little money (relatively) and making huge profits. Where was their piece? This led to "The Great Flexing" (trademark pending) - the golden age where broadband companies throttled service and started shaking down Internet companies. The lack of regulation on broadband played to their favor. So, the FCC decision is not turning their back on Internet freedom, but turning their back on greedy cable executives. Ajit's dissent goes on to say: The Commission’s decision to adopt President Obama’s plan marks a monumental shift toward government control of the Internet. It gives the FCC the power to micromanage virtually every aspect of how the Internet works. It’s an overreach that will let a Washington bureaucracy, and not the American people, decide the future of the online world. The decision gives the FCC the authority to treat broadband as it does the telephone wires. If Ajit is arguing that this translates into giving the government the ability to control every aspect of the Internet, then he should provide evidence of how the government has manipulated every single aspect of the telephone industry. Again, the FCC is saying treat broadband like the telephone. So, there should be plenty of evidence of the government micromanaging the telephone market (if the dissent is correct). His dissent goes on: One facet of that control is rate regulation. For the first time, the FCC will regulate the rates that Internet service providers may charge and will set a price of zero for certain commercial agreements. The Commission can also outlaw pro-consumer service plans. If you like your current service plan, you should be able to keep your current service plan. The FCC shouldn’t take it away from you. Consumers should expect their broadband bills to go up. The plan explicitly opens the door to billions of dollars in new taxes on broadband. One estimate puts the total at $11 billion a year. Consumers’ broadband speeds will be slower. Compare the broadband market in the U.S.to that in Europe, where broadband is generally regulated as a public utility. Today, 82% of Americans have access to 25 Mbps broadband speeds. Only 54% of Europeans do. Moreover, in the U.S., average mobile speeds are 30% faster than they are in Western Europe. This plan will reduce competition and drive smaller broadband providers out of business. That’s why the plan is opposed by the country’s smallest private competitors and many municipal broadband providers. Monopoly rules from a monopoly era will move us toward a monopoly Unfortunately, there has been a living lab (of sorts) for well over a decade, where some countries have opened up their Internet (with similar legislative tools just used by the FCC) and American, which has remain closed. The results for those other countries: lower broadband rates, improved service and service options, lower bills (compared to the US) for better service, faster broadband speeds, and more competition in the Internet Service Provider business. All of which are the complete opposite of what Commissioner Pai's dissent claims. The evidence shows that the dissent's assertions are not grounded in reality. Larry Lessig's talk (in 2010) about American's broadband problem (below) outlines the approaches taken by the American government and the European Union and the impact they have in each environment. You have to watch it. Broadband is cheaper, faster and better in Europe than in the United States. All because Europe did what the FCC just recently did decades ago. Ajit's dissent continues: The Internet is not broken. We do not need President Obama’s plan to “fix it.” The plan in front of us today was not formulated at the FCC through a transparent notice-and-comment rulemaking process. As The Wall Street Journal reports, it was developed through “an unusual, secretive effort inside the White House.” Indeed, White House officials, according to the Journal, functioned as a “parallel version of the FCC.” Their work led to the President’s announcement in November of his plan for Internet regulation, a plan which “blindsided” the FCC and “swept aside. . . months of work by [Chairman] Wheeler toward a compromise.” The plan has glaring legal flaws that are sure to keep the Commission mired in litigation for a long, long time. I agree that the Internet is not broken. However, the ecosystem required for its continued growth was and that is what the FCC addressed. I have no insight on the rulemaking process, so I cannot comment on that part of the dissent. I also agree that the current set of cable companies will continue to sue in order to get their way. However, I think their time will be better spent finding new ways to partner and collaborate to create additional revenue streams; rather than trying to tax the existing successful players and increase the barrier to entry for emerging startups. All that being said, I am not a lawyer nor claim to be one. However, I do know technology. I am an expert and a student. In my mind, I want to think that Ajit had excellent technical guidance when forming his position on this issue. However, I am reminded that different generations have different views and levels of understanding on the issue. Hey! Old-school civil rights organizations got it wrong too. More here. What do you think? Let me just say upfront that I personally think that the term sharing economy is a bunch of marketing and PR bullshit. My more diplomatic self would say that the sharing economy (as the media tells it) is a bastard misrepresentation and it will have consequences that will be written off as unintended in the future, but that are presently known by the current architects of this economy. The sharing economy (aka the peer-to-peer, mesh, or collaborative economy; also called collaborative consumption) is formally described as a socioeconomic system built around the sharing of human and physical resources. It includes the shared creation, production, distribution, trade and consumption of goods and services by different people and organizations. These systems seek to empower individuals, corporations, non-profits and government with information that enables distribution, sharing and reuse of excess capacity in goods and services. A common premise is that when information about goods is shared, the value of those goods may increase, for the business, for individuals, and for the community. Unfortunately, this vision of a sharing economy and the current companies that are sold as embodying this economy are at odds with each other. Businesses, like AirBNB, TaskRabbit and Uber, are often touted as the success stories of the sharing economy - unleashing the potential of the ordinary citizen to help his or her fellow citizen (for financial gain). However, the motives of these businesses are very clear - how to capitalize on cheap (if not free) resources, i.e. humans, their time and their possessions, to make a profit by decentralizing (or deregulating or disrupting) an existing sub-optimal industry or industry sector. The idea is simple and brilliant.

I call this a Gig Economy. Everyone has a gig. It is a new class of service industry where workers are expected to operate like micro-businesses with full risk, no union representation and very little safeguards. The Gig Economy (or the Share-The-Scraps economy, as Robert Reich calls it) is far different from the Sharing Economy and it is evident to me that one is playing off the goodwill and promise of the other to move itself forward. If I can see it, then others can too. The first interesting phenomena is that this economy is projected to be at least twenty times bigger than it currently is within the next decade; settling in at revenue growth around $355 billion dollars. And though there is discrimination in this gig-gy environment (see here), minorities are still drawn to it for several reasons.

They are drawn to it as service consumers, because it offers a higher level of service that they were receiving in the industry before. Ask a black man having a night out in Washington DC to compare his "taxi" experience now versus when he did the same thing in 2007. I guarantee you that the majority of responses would indicate that the presence of Uber and Lyft has given him a lot of freedom and reduced his stress level. Minorities are drawn to this Gig economy as service providers, because it is an avenue that offers less institutional roadblocks to entry. A hispanic woman from the projects with few options and lots of ambition can easily find a well-paying gig that would help her tremendously in getting a better life. Is this good or bad? I leave that up to you to decide. I just want us to all be fully aware of what is happening. Eyes Wide Open. What are your thoughts? |

Dr Tyrone Grandison

Executive. Technologist. Change Agent. Computer Scientist. Data Nerd. Privacy and Security Geek. Archives

May 2018

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed